Railroad Grand Masters Playing 50 Opponents Simultaneously

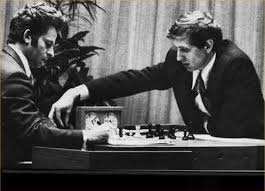

Bobby Fischer is considered by many to be the greatest chess player who ever lived. I remember watching with interest, back in 1972 – at the height of the “cold war”, when he played the Russian Chess Grandmaster Boris Spassky for the world championship. (Yes, I’m that old!)

Seen as symbolic of the political confrontation between the two superpowers, it was called “The match of the century.” At the time, the Soviet Union had dominated in chess for the previous twenty-five years.

Included in the prime time media frenzy about our American chess genius was a story and photo of a previous exhibition where Fischer played 50 opponents simultaneously.

With that image in mind, I participated in, watched, and listened as a fierce storm blew into the Wasatch Front and instigated a railroad chess exhibition, where our Railroad Grand Master Controllers were suddenly called to play their own 50 opponents simultaneously.

I was on my regular work, waiting to depart from Ogden with my train, as we were just beginning our peak 30 minute service for the afternoon commute. At about 3:30 pm, just minutes away from my departure time, while watching the severe thunderstorm roll in from the west, the radio came alive with calls from Control. “UTA Control to any MOW in the Clearfield/Layton area.”

MOW was a few miles away but responded to the call. Power was out at the Layton south control point. This was soon followed by the report of the track “showing occupancy” between Clearfield and Layton. More calls continued describing more problems up ahead of me. I didn’t know it at the time, but Utah had just experienced two tornados right ahead of me. Right here in Utah, where even a single small tornado is a rare event.

Before I could get the 20 minutes down the line where this troubled area was, many supervisors and MOW personnel were on the way to inspect the track and man the switches that would now need to be operated manually. However I-15, the freeway along our track, also suffering from the blast of the storm, was gridlocked and our reinforcements, now caught there, were going no where fast.

By the time I arrived at Clearfield Station the “Occupancy” reported earlier had cleared and I was given the directive to proceed at Restricted Speed almost all the way to the next station, which was Layton. Where 79mph was normal, this was a rather long way to go at a maximum speed of 20 mph. But with the mandate to “be able to stop within half the range of vision” of a whole list of possible hazards ahead of me, I went slower than that for much of it.

There were lots of debris strewn along the railroad right-of-way that Union Pacific and FrontRunner share through that stretch. Mostly tree limbs and other small items strewn up very close to the rails. I had to proceed slowly enough to sort out what I was seeing, determine if there was anything that might cause damage to the rails or the train, and be able to stop well before encountering such a threat.

Eventually, I came to a mostly intact metal roof blown from a nearby building. It was just off of our rails but it covered some of the UP tracks. This was the most likely cause of the earlier “Track Occupancy” that originally showed up in the Control Room. I’m sure that continuing wind from the storm had moved it just off of our rails before I had arrived, allowing my train to cautiously venture beyond the Clearfield Station.

After I finally arrived at Layton Station, my train had to hold there and wait for the northbound train, which was now caught behind the dead South Layton signal and switch that splits a siding off the mainline track so trains can “meet” at the station.

Because of the traffic gridlock on I-15, MOW and the Operations Supervisors still hadn’t arrived to help. So the Engineer of the northbound train had to tie down his train, and go down on the ground to manually throw the switch for his train to enter the siding into the station. Besides the process of unlocking it, taking the switch out of automatic and manually cranking it to the proper position, specific radio protocols with the controllers must be followed throughout the process. Once this has all been completed and the engineer is back on his train, which has once again been made ready to go, he now communicates with Control as they follow another set of radio protocols allowing his train to proceed past the improperly displayed signal.

With my train moving from Clearfield Station to Layton Station at mostly 10-20 mph where 79 mph is normal, and the wait while the northbound train worked his way through his signal and switch issues to finally make it into the Station, by now we were really running behind schedule.

The MOW first to respond finally found some back roads that got him to the troubled switch and signal up ahead of me just in time to manually line the switch for my southbound movement so I didn’t have to tie down my train and do it myself. I still had to go through the red signal by-pass procedures which of course continued to delay us even more, but we were finally moving away from the worst of the storm zone.

Problem was, my train was now so far behind schedule that I was out of sync for meeting each of the oncoming northbounds and so I repeatedly had to wait. Now, the numbers of waiting passengers at each station swelled because it had been such a long time since a southbound train had been through. This further delayed my progress as these many irate passengers overcrowded into my late train. By now I was so late that passengers, used to boarding the train behind me, arrived at each station thinking I’m trying to depart a few minutes early.

UTA Warm Springs Control continued to scramble, trying to manage everything going on and somehow get the trains back on schedule. Among many other things I’m sure they were doing, I observed or was aware of the following.

- With an increasing number of trains now running substantially late, they added at least one extra train to help take up the headway for the many commuters (our King) trying to get home.

- Extra trains and regular trains falling back to later headways of course increased the management complexity as the already busy single track corridor was even more crowded and the crews on various trains were working other than their normal headways and trains.

- At some point, these crews needed to be shifted to their correct work positions so they could end their tour of duty at whatever location their work ended and before exceeding their maximum allowed hours of service.

- Several signals continued to malfunction for some time, requiring Control to continue directing the ground personal who were manually “throwing” the switches, along with the cumbersome process required of them for the trains to proceed after following the “Red Signal By-Pass” radio protocols.

- Along with the signal problems there were three “Crossing Protections” that stayed in affect for many hours. Each of these crossing protections were separate “Mandatory Directives” that had to be given to each train (when stopped so they could be written down) and then read back to confirm that each detail was exactly correct. The train engineer then had to proceed up to each crossing at a specified speed, while sounding a specified horn sequence. Control needed to keep track of which train and which engineer had received each crossing protection. Because these crossing protections continued for so long, Control needed to reissue the crossing protections to the “new” engineer after the crews rotated out but before they reached the crossings under protection. When the crossing protections were finally released, Control needed to contact every train and every engineer still on duty to void each crossing protection.

- Along with keeping track (and directing) of the mayhem on the mainline, the required paperwork they now needed to keep up on was just as intense. Along with what I’ve already mentioned about documenting “Crossing Protections”, MOW’s access permits to the mainline track via “Track and Time” and “Fowl Time”, keeping track of what trains were running in what headway, and who the crew members were on all these train in this now mixed up system, they now had reports to complete every time a train departed a station more than 5 minutes late. In this storm of delays, that alone was a mammoth task.

- The feedback coming from UTA’s customer service department, through instant mediums such as direct customer cell phone calls and Twitter comments needed to be taken into account as decisions were made about whether or not to hold an already late train for transfers from light rail or bus. Most customers were unaware of the challenges to the whole system caused by such a brutal storm on our north end, especially those on the south end of our alignment.

- At least several of our trains (now working later assignments than they were intended to) needed to be taken out of service for refueling and time sensitive inspections. This was accomplished by making train swaps with “fresh” trains that were ready to go.

- Also of course getting the proper train crews on their proper trains was an on going process that took many hours to complete.

It was over 8 hours after the storm (after I had gone home) when I finally stopped listening to the radio chatter. Even then, sorting out the aftermath continued. The three crossing protections, scattered in the storm zone, were still in effect when I turned off the radio and went to sleep. It literally took all night to get everything working properly again.

I’m sure when 21 year old Bobby Fischer finally finished his chess exhibition of playing 50 competitors simultaneously, or when 29 year old Bobby Fischer won the “Game of the Century”, he went home, kicked his feet up, open a cold one and said, “Wow, what a game!”

Even though it might be fun to play Chess, “Railroad Control Room style”, for now I’ll leave it to the Railroad Chess Masters of FrontRunner. Because at this point, I’m having too much fun just driving the train.