In the months since licensing as a railroad engineer, my work block has mostly consisted of overnight work on the northern half of the FrontRunner alignment. This work shift includes taking the last train of the day to Ogden at night where I perform necessary safety tests and inspections. I then tie down with the train for a few hours, before taking the two early morning trains farther up north to Pleasant View on Union Pacific alignment. (This requires two of us, one serving as conductor and the other one as the engineer.) I then bring my train back south with early morning commuters headed for Salt Lake and other points south.

My second Tri-annual bid for work has now left me with this same piece of work at least until April. And the repetition of going through this same workday, day after day, has mentally placed me in the Bill Murray movie “Groundhog Day”.

Being caught in the “same day loop”, Phil Connors eventually out grew his bungling, self-centered; second rate self, into a very talented and rather nice guy. I’m hoping for something similar as I relive my own Groundhog Day… day in and day out… week by week… month after month.

Currently, a small piece of my repeating Groundhog Day is as follows. Whereas the movie character Phil Connors nightstand alarm clock clicks from 5:59am to 6:00am and Sony and Cher start singing “I’ve Got You Babe”, my watch is sliding from 3:59am to start the last active portion of my work day. Mine is to the rumble of the waiting locomotive instead of Sony and Cher singing their signature song.

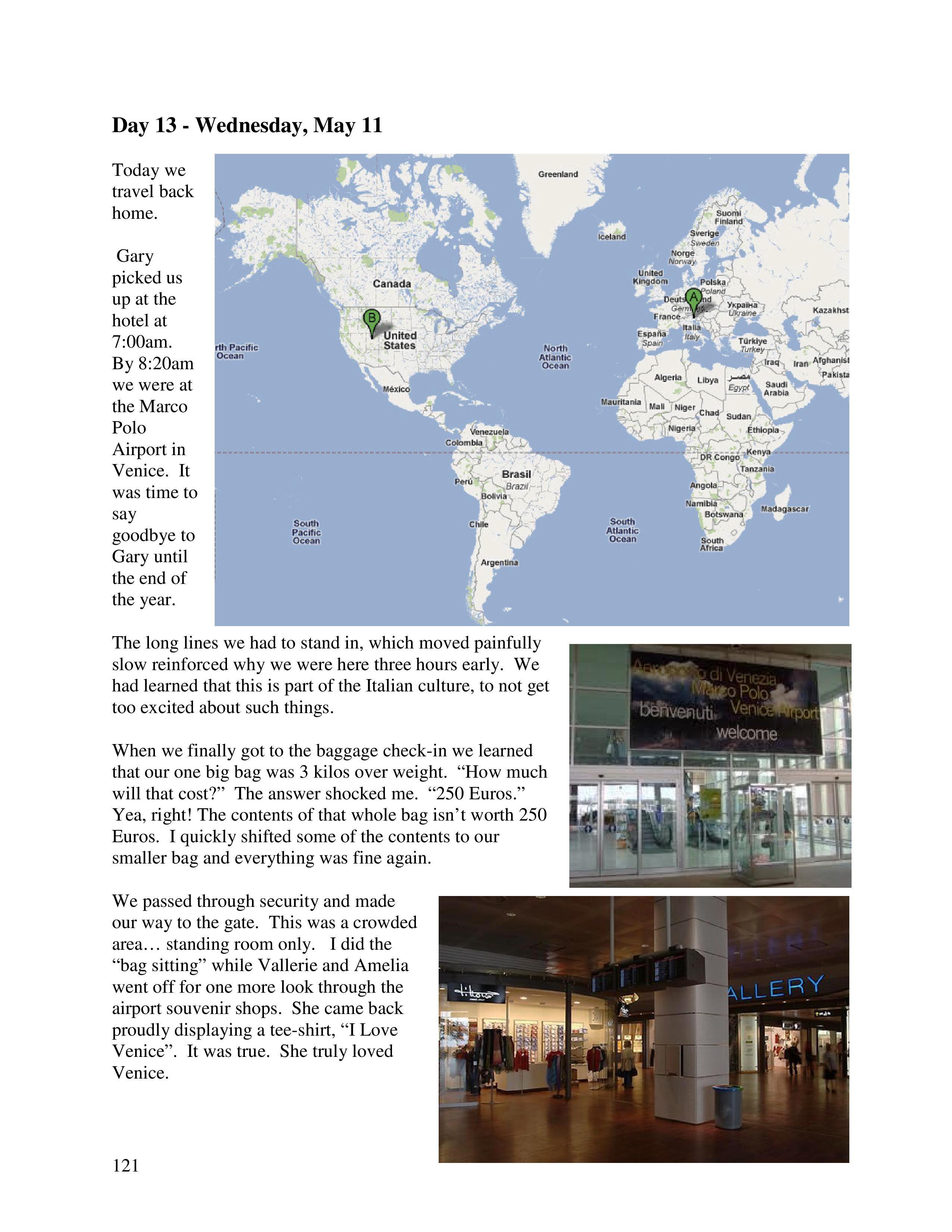

4:00am – I look across the Ogden Station Platform from my locomotive to the locomotive for Train 3. James stands up, dons his safety vest, gathers up his gear and climbs down out of his Locomotive. He is headed back to release the hand brake at the other end of his consist and make ready for our departure. I likewise gather my things together, climb down from my Train 5 Locomotive, enter the back door of Train 3’s Loco and release its handbrake. I then proceed up to the cab and settle into the Engineers seat and begin the preliminary paperwork.

4:10am – James joins me in the Loco cab and we complete the Union Pacific Job Briefing Checklist, review the daily UP Track Warrant, and begin the Conductor Report. This daily routine doesn’t take long and we are soon down to small talk while waiting for our departure time.

James tells of his latest weekend – Surfing on a California Beach (his flight attendant wife gives him travel perks), while I desperately struggle to think of something from my “weekend” that I can mention so he doesn’t realize that I have no life. In the pause in dialog, James brings up sports. I finally have to admit that I don’t follow sports… have always just worked. I’m thinking, “I do actually have a life… it includes long distance running on empty 2:00am city streets… trying to write… playing my harmonicas…” But those seem like awkward conversations as well. What kind of eccentric runs up and down city streets in the middle of the night for fun? And it is assumed that anyone who plays the harmonica, plays “Blues Harmonica”. I don’t… can’t… OK… the truth is I play ON the harmonica more than actually playing the harmonica. So I don’t bring it up.

4:22am – Time to go… bring up the cab signal… get a door loop… headlights… gen field on… radio call to Warm Springs control… bell on… reverser forward… throttle notch one… and we move forward toward the end of the platform where we lose our cab signals and have to stop to reset them for movement in Union Pacific territory.

I’ve made this same trip to Pleasant View many times. It is all exactly the same except it’s always different. The different trains vary in how they handle… some more power than others… they all brake differently than how the last train braked… I’ll have to quickly get a feel for this one and make adjustments accordingly.

4:25am – As I approach our first control point… CP G001, I need to slow down to 25mph… Both James and I call out the signal (as required) “Clear”. I give the brakes a minimum set… they seem to glide along too far and then grab a bit later. I’ll have to make adjustments to how I brake with this train. I call out my speed to James (the conductor) who makes the necessary notes in the Conductors Report. He is recording the required info on the UP radio for this signal. We both call out our next signal as it appears in the distance… “Advanced Approach”. I reach my landmark (an electrical box along the alignment) and notch up to speed the train to 55mph.

4:27am – James makes his UP radio transmission… “UTA Train 11 at CP G003, Advanced Approach – Out”. My speed is now 55mph and I drop back to “notch 2”. I know that this exact timing and combination of power will maintain our speed at exactly 55mph until we come around the corner and can see our next signal, “MP 4.6”.

4:29am – We both call out “Approach Restricting” at the same time. James makes his radio call and I make a minimum brake set. “It took me a long time to get this one right. (Kind of like Phil Connors repeatedly stepping in the slush filled pothole in Groundhog Day.) I need to slow to 40mph very quickly but was always slowing too much because the track runs steeply uphill here. I have finally learned to apply only a minimum set and release at 45mph and then immediately go to notch 4 on the throttle. As we roll up to the control point we always seem to be going too fast, but the train continues to slow and now the speed is always exactly 40 as we pass it, with enough momentum to maintain this speed until our next control point. (This is where I really start to feel invincible like “Groundhog’s Phil” stepping in to save the pending wedding or the choking man in the restaurant.)

4:32am – At CP G005, I need to be slowed down to no more than 15mph. This one should be easy, but the variation in braking from train to train gets me when going this slow. This time I cross the signal going 13mph. This is well within the speed requirement, but I wanted perfection at maximum authorized speed… that’s the game I play over and over. That and the perfect station stop. I’ve got a ways to go on that one too. Since licensing, I have never had to make the radio call of shame to tell control that I’m a door long, but too many of my stops could be classified as sloppy.

4:34am – This station stop was perfect. We now perform the needed operations to “turn the train” which means that we will be operating from the other end of this same train as we depart south bound in 18 minutes.

I will pass this same 12 minutes of Union Pacific track another 3 times, doing the same thing before arriving at Ogden Station where I begin collecting the masses of commuters headed south.

6:03am – I bring my “Train 5” to a stop on the Ogden west platform to the gathering group of southbound commuters. My conductor, from our just completed “Pleasant View” trip has gathered his bags and the special UP radio, and exits the train. As a southbound train, I am operating in the “Cab Car”, which is on the opposite end from the Locomotive. Down here, I am more visible to my passengers, and they to me. While passengers are boarding, I open the operator’s window to greet my newly boarding Train Host, who will be back with my passengers as we proceed south. “Good morning Joan.” “Good morning Ron.” I watch from this opened window while passengers continue to board. Though I don’t speak to these people personally, I know these passengers very well by now. The same man in the dark business suit (now also with an overcoat) who always carries a newspaper under his arm gets on in the Cab Car and takes his seat behind my operators compartment. He always sits facing away from me, and spreads in his lap newspaper as if to share with anyone looking over his shoulder. (He will ride to North Temple Station). The woman, always wrapped from head to toe, (even in warmer weather) takes her seat right behind my operating compartment. This seems strange to me, because this is the coveted seat, the only seat on the entire train where the passenger can see what the engineer sees while the train is moving down the track. But she never looks up. Her face is always buried in the broad collar of her coat, so that only her eyes and nose can poke out at her cell phone which is the continual focal point until she exits the train at Salt Lake Central Station.

I could go on with each passenger within my view every day, but you get the Idea.

6:07am – It’s time to depart, and I am standing at the open window telling the last three commuters, who are still off in the parking lot but scrambling to make the train, to hurry to the nearest train door. It’s always the same three people, and they always seem surprised that the train is ready to leave at 6:07am. (These 3 commuters don’t know this but if I haven’t started to move the train yet, AND they are hurrying… like running if capable… I will wait for the latecomers. But if it’s time to go and they are just walking along in no hurry, I’ll leave them behind every time.)

6:08am – Finally, the last late comer has boarded the train and I close and lock the doors. Now I need to try to make up for my late departure. My first three station stops are rather tight on the schedule, so now I feel like Scotty from Star Trek fame trying get all I can out of the locomotive as we build momentum and climb the Ogden “Flyover” which bridges over the top of the many Union Pacific tracks below.

I know the exact power setting and adjustment as I at first build speed while climbing the “Flyover” and then descend, all while maintaining the maximum authorized speed. A speed which keeps changing as we proceed south.

6:15am – I’m still creeping toward Roy Station on my 15mph cab signal. The same late comers are cutting in front of my train at the platform. I’ve got my hand over the horn button ready to “warn away” any more attempted crossing in front of me as I near. The same man stops and waits. Once he was too close when he crossed. I had tapped my horn. He first completed his run in front of me and then turned and shook his fist at me. I’m sure he had a few choice words for me as well. Now he still comes late as my train approaches, but he waits… glares. I’m thankful that he is alive and well and can glare at me every morning. I’ve heard stories from other engineers where the outcome wasn’t this happy. Of course I make sure he is on board before I depart.

This is the first of three “train meets” I’ll have before arriving at North Temple station. On our single track, we have to meet the trains headed in the opposite direction where we have sidings or at stations where we have two tracks. Some engineers make it a competition to beat the other train to the “meet” and others not so much. I guess I’m competitive that way. Everything I do as I move south is all about beating the other train to the meet.

6:24am – Clearfield Station… I depart almost one minute late at nearly 6:25am… still trying to make up for my departures from Ogden and Roy.

6:30am – Layton Station… train meet with the northbound… depart on time.

6:38am – Farmington Station… I arrive 2 minutes early and can relax a bit. We depart on time at 6:40am.

6:46am – Centerville Siding waiting for the oncoming Northbound train.

6:51am – Woods Cross Station… one minute late because of waiting for northbound train at the Centerville meet.

7:01am – North Temple Station. This is where I am relieved from duty. I just take a seat on the same train and as a passenger now, and let my replacement engineer take me home.

It takes a little less than an hour go from Ogden to North Temple Station. Of course I could tell all, detailing my awesome train handling skills as I meet difficult sections of track, how I can manage the brakes and throttle ahead to provide perfect timing in the trains delayed performance. I could tell stories of passengers from each station. Like how at Clearfield Station, everyone is lined up in perfect single file at each marked spot on the platform for a door. Yes, those are 8 perfect single file lines waiting for me to stop a door directly in front of each one. (No pressure there on making a perfect station stop!) I could brag about rolling into the “Centerville Siding” early enough to get my train out of the way so that the “Northbound” train won’t get a “Cab hit” which would slow it down. But, this is enough… you get the idea.

At least up here on the north end of the FrontRunner alignment, I feel more like the Groundhog “Phil Connors” at the party (after he has honed his talents, as well as his social skills, to perfection) when Rita (who is surprised at his suave interaction with everyone at the party) asks Phil, “What did you do today?” Phil nonchalantly replies, “Oh, same old same old.”

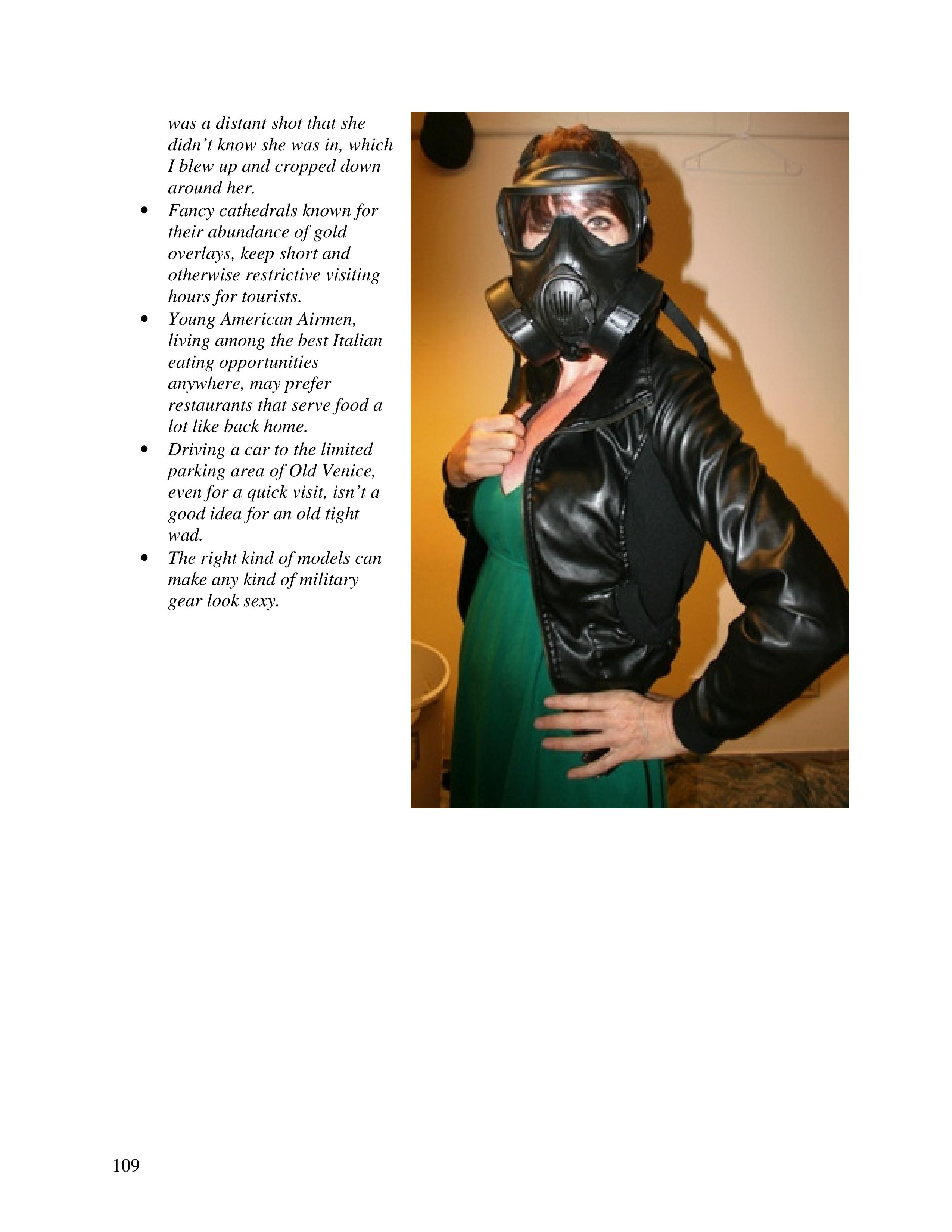

If I ever get to drive the trains on the south end of our alignment, I probably won’t remember what to do. I’ll be like the bungling Phil Connors on his first few days of his Groundhog Day loop again. But for now it’s looking like that by next April, I’ll be operating my Train 5 on the north end like Groundhog Phil playing the piano at the Punxsutawney Celebration.